For my exemplars, I have chosen the following three designs:

- Bamboo Wall House by Kengo Kuma (chosen apprenticeship)

- Mooloomba Beach House by Brit Andresen and Peter O'Gorman

- Marika-Alderton House by Glenn Murcutt

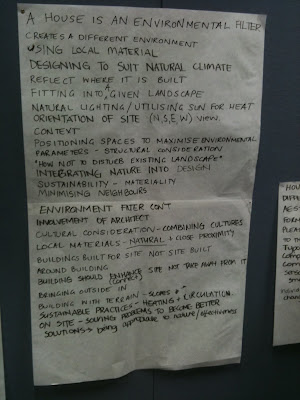

The reason why these three particular works appeal to me more than the substantial list of others provided to me is because they all share a common link: their close relationship to the environment around them, and a technique to designing which dealt with the topographical constraints by altering the design, not the topography, which was mostly seen in the Marika-Alderton House and especially in the Mooloomba Beach House. Therefore, when addressing the concept of a house being an environmental filter, a container of human activities, and a delightful experience, the separate designs at times come together with their similarities on issues such as climatic constrains etc.

Note: citations have been made where a direct statement is being presented, otherwise, the information I have analysed through sources which haven't been quoted in the text have cited in the reference list as they were a source for the general information I have presented.Bamboo Wall House - Kengo KumaFigure 1

"All my buildings are experiments; I try to listen as carefully as possible to the site and consider how best to respond to it. Consistency is not so important" (Webb, 2003, p. 66). The essence of Kuma's architecture derives from his desire to 'erase' architecture, in that he "dissipates as much as possible the boundary that opaque walls provide. In making an anti-object he erases the primary characteristic of architectural form and embraces architecture as a sequence of

human experiences. He sees the act of architecture not as an object but as an

'experience and phenomenon'" (Weiner, 2007, p. 248). This provides a direct link to the notion that a house is an

'environmental filter', a container of 'human activities', and a 'delightful experience' as Kuma's intention is to address these concepts in his architecture in order to make it truly delightful.

However we must refer back to Kuma's initial thought of erasing architecture in order to fully comprehend how these three aspects tie into his architecture. If architecture is erased, how do the three spacial qualities exist without form? As Weiner (2007, p. 249) questions, "this would be a place without quality. Does architecture without quality create place without quality? Is the erasure of architecture also the erasure of the possibility of the topos of architecture? Kuma's representation of architecture as deletion within an environment or surrounding challenges the notion of quality and its relationship to architecture and place." Therefore, the erasure of architecture does not necessarily lead to the diminishing of the three elements of architecture discussed previously, yet it provides a deeper element to the design if the architect is able to incorporate those three elements to make a space whole.

Kuma's design for his 2002 'Bamboo Wall House' borrows its low horizonal profile from the Great Wall itself. But while the Wall symbolizes permanence, solidity, and exclusion, Kuma's bamboo wall is meant to suggest the easy transfer of light and breezes from one side of the house to the other, as well as a certain lightweight, unfinished, and even fragile quality. The house is also designed to mimic the way the Great Wall runs almost endlessly along the undulating ridge line without being isolated from the surrounding environment. Kuma has also shown how luxurious sustainability can appear if put in the right architectural hands through his eco-friendly use of the local resource bamboo, which can be used both as light filters and as wallpapers. Kuma's architecture is made through the sheer digital preponderance of numeration, elements, parts, pieces and thei r repetition. he wants to break down or 'crush; the materials of architecture to the level of particles to achieve a fusion with nature. He calls this 'particalizing'. This affect is generally achieved by fabricating exterior walls that are more like open screens, membranes or a series of verticle or horizontal louvers rather than solid walls, as can be seen through the use of bamboo as his 'walls'. The building is a series of platforms and stairs depressed into and at times slightly breaking the ground plane. Exposed faces of architectural elements such as walls that protrude above grade and the line of the vegetation are minimised to the greatest extent possible. In a sense the building has no elevations but only visible edges. It reads like a tabletop without legs. The inhabitable portions of the building lau underground further emphasising the erasure of architecture. Kuma avoids making elevations that prominently protrude above the horizon, as can be perceived by the house being flat and under the impression of 'small' compared to the vast mountainous surrounding topography. By this procedure architecture itself is dis-qualified and de-natured, environment replaces nature and architecture lies buried in

absentia.

Mooloomba Beach House - Brit Andresen and Peter O'GormanFigure 2

Secluded within the Stradbroke Island beach community at Point Lookout, is Brit Andresen and Peter O’Gorman’s 1996 'Mooloomba Beach House'. The Mooloomba Beach House manages to functionally include the three elements of a house as an environmental filter, a container of human activities, and a delightful experience through its intricate design and relationship to the surrounding environment, climatic and topographic constraints, and overall functionality which will be further elaborated upon as follows. The project gently heightens the sense of being in a particular landscape and in a climate where one can merge outside and inside a great deal of the year. The site is always acutely observed, with topography and vegetation enlisted as architectural elements. Sitting on an elevated north facing site, the two storey building is composed of a series of rooms of varying levels of enclosure or exposure, stretched along the length of the sloped boundary. "In this house, living takes place amongst a wild garden of Banksias and Boxtrees, wrapped by a light framework that houses the more complex requirements of

dining, sleeping, bathing and preparing food. Following the movements of the micro-climate, the house faces the sun while the eastern wall is a filtering edge to the breezes that swing from southeast to northeast. This house is designed to accommodate a simple series of holiday living requirements:

to sleep, eat, bathe, read, and relax" (National Timber Education Program, n.d., p. 15).

The site is dominated by garden, and edged by building. The siting strategy places the house along the long western boundary, so that the living spaces look east across the garden. The two-storey building is composed of two systems of framing and several different ‘characters’ of construction. These construction differences throughout the building are linked to the way that the building is organised, occupied and sited . The garden boundary side of the building is the structural core, housing the living requirements for sleeping, bathing, and preparing food. The western side of the house is slung between the structural core and a series of irregularly spaced cypress poles. It interacts with the garden through a free-form combination of structure and cladding that lightly frames a series of multipurpose ‘outdoor’ living rooms. The living room is an insulated, double skin space designed with an increased potential for enclosure, as a ‘warm’ place during cold weather. Sleeping boxes, large enough for a bed and a little storage, are off a narrow open walkway on the upper level that overlooks the garden side of the house. The spaces are tight modules fitted within strict framing based on the dimensions of standard plywood sheets. The house is large, yet has only sixty-five square metres of internal space. Using a single skin structure in response to the climate, fixing uncut, standard size sheets of plywood to the building, using locally sourced Cypress poles, and maintaining minimal kitchen and bathroom spaces, are also factors that have contributed to low costs.

Marika-Alderton House - Glenn MurcuttFigure 3

“To touch this earth lightly” (Barreneche, 2002, p. 27), the environmentalist philosophy of Glenn Murcutt, is highly developed in his prototype housing for the Australian Aborigines: The Marika Alderton House. Extensive consideration of climate is developed in the Marika Alderton House concerning both specific and large-scale climatic issues. Wide eaves shelter the house from the sun, and pivoting tubes along the roof expel hot air which rises and vertical fins direct cooling breezes into the living spaces. Because the structure rests on stilts, air furthermore continues to circulate underneath and helps cool the floor, in addition to elevating the house in order to keep the living space safe from tidal surges.

Two primary specific issues surrounding the Marika Alderton House include its immediate cultural and social climate under which it was built and the specific weathering patterns associated with the site. More importantly, in his project Murcutt directly addresses the greater climatic issues of the house, in that it is in a hot, humid, tropical climate with ventilation being the primary concern lying behind the comfort and sustainability of the Marika Alderton house. The intentions for the Marika Alderton house are product of the immediate cultural and social climate of Northern Australia at the time of its conception. The Marika Alderton house was designed as a sustainable and economical prototype to be used by the Australian authorities to house the Aborigines. Providing an example of the benefit Murcutt's design has made, reiterates that "Aborigines were housed by Australian authorities in lit solid masonry boxes, which were poorly ventilated and uncomfortable. In the hot, humid and tropical climate of Northern Australia, these houses were often abandoned or destroyed by the Aborigines, as they were inappropriate and unusable" (Henderson, n.d., p. 2).

Murcutt develops the comfort of the building through his analysis and sensitivity to both the specific weathering patterns of the immediate site and of the greater climatic region.

As a starting point for his extensive climatic research, Glenn Murcutt began to take into consideration the specific surrounding weather patterns of the proposed site for the Marika Alderton house. The site lies in a cyclone zone and due to the high-speed cyclonic winds over the ocean the site is also prone to flooding throughout the year. Taking this into consideration, the steel structure of the Marika Alderton House was designed to be strong enough to resist the cyclonic winds. From the specific weather conditions of the immediate site to architect Glenn Murcutt’s prime climatic concern, the Marika Alderton house evolves into a completely environmentally aware and sustainable shelter. The Marika Alderton House lies in a hot, humid, tropical climate, and in such a climate, ventilation becomes the dominating factor in creating a comfortable and enjoyable place of inhabitation. Murcutt integrated many ideas and tactics to promote ventilation in the Marika Alderton house through his design of the houses’ walls, plan, floor and roofing elements. The shutters tilt down to allow for more shade as needed, they filter percolated light into the space, allow for airflow when open, tilted or fully closed, and create privacy when needed. Also, lining the exterior walls are large protruding fins. These fins, oriented towards the ocean, slow down, capture and redirect the cooling and fragrant ocean breezes into the interior spaces of the house creating an enhanced and more comfortable environment.

The plan of the Marika Alderton house is designed so that the sleeping quarters are to the southwest of the house. As a result of the buildings’ Southern Hemispheric orientation, in the evening, the southwest corner proves to be the coolest part of the building, which provides for more comfortable sleeping arrangements. Also to induce a cooler sleeping environment, the sleeping platforms are raised 2m off of the floor so that maximum air circulation underneath the bed can be attained. Following the remaining plan of the house, the living, kitchen and laundry areas are located in the northeast corner so that in the morning, when the residents do most of their laundry, food preparation and work exercises, that end of the house is coolest. The floor of the Marika Alderton house is raised up off the ground typical of hot humid vernacular architecture so that air can circulate underneath the building and so that the house itself does not absorb into the living environment, any of the heat which radiates from the earth in the evening. In the case of the Marika Alderton house, Glenn Murcutt magnifies this vernacular example of hot humid architecture, in that several gaps between the timber floor decking exist so that cool air from the exterior environment can flow directly up into the house from underneath providing a cooler environment for the inhabitants.

References

Architecture Australia. (2002, March/April). New directions in Australian architecture (2001). Bingham-Hall (ed), 60-64.

Retrieved March 5, 2010, from http://static.royalacademy.org.uk/images/width370/great-bamboo-wall-3249.jpg

Aymonino, A., Mosco, V.P. (2006). Contemporary Public Space Un-volumetric Architecture. Milano: Palazzo Casati Stampa.

Barreneche, R. (2002). Murcutt wins Pitzker prize. Architecture, 91(5), 27.

Retrieved March 5, 2010, from Academic Search Elite database.

Beck, H., Cooper, J. (2004). Figure 3. Arcspace.

Retrieved March 20, 2010, from http://www.arcspace.com/books/Murcutt/murcutt_book.html

Department of Architecture. (2008). Figure 1. National University of Singapore.

Retrieved March 20, 2010, from http://www.arch.nus.edu.sg/50/lectures/kengo-kuma/index.html

Dovey, K., & McDonald, D. (1996). Architecture about aborigines. Architecture Australia, 85(4), 90.

Retrieved March 6, 2010, from Academic Search Elite database.

Henderson, K. (n.d.). The Marika Alderton house. University of Waterloo, 1-5.

Retrieved March 13, 2010, from http://www.architecture.uwaterloo.ca/faculty_projects/terri/pdf/Henderso.pdf

Keniger, M. (1999). Figure 2. The University of Queensland Library.

Retrieved March 20, 2010, from http://digilib.library.uq.edu.au/view/UQ:13466

Kuma, K. (1999). Kengo Kuma: Geometries of Nature. Bergamo: Poligrafiche Bolis.

Marika Alderton House. (2009). Architectural Record, 197(5), 105.

Retrieved March 4, 2010, from Academic Search Elite database.

National Timber Education Program. (n.d.). Mooloomba beach house.

Retrieved March 5, 2010 from Academic Search Elite database.

Stand, A., & Hawthorne, C. (2005). The Green House. New York: Princeton Architectural Press.

Tropical House. (1996). The Architectural Review, 200(1196), 40.

Retrieved March 4, 2010, from Academic Research Library.

Webb, M. (2003). Particle theory. Architecture, 92(3), 66.

Retrieved March 4, 2010, from Academic Search Elite database.

Weiner, F.H. (2007). Architecture as such: refutations and conjectures of quality in the work of Kengo Kuma and W.G. Clark. Arq:

Architectural Research Quarterly, 11(3-4), 245-253.

Retrieved March 4, 2010, from Academic Research Library.